|

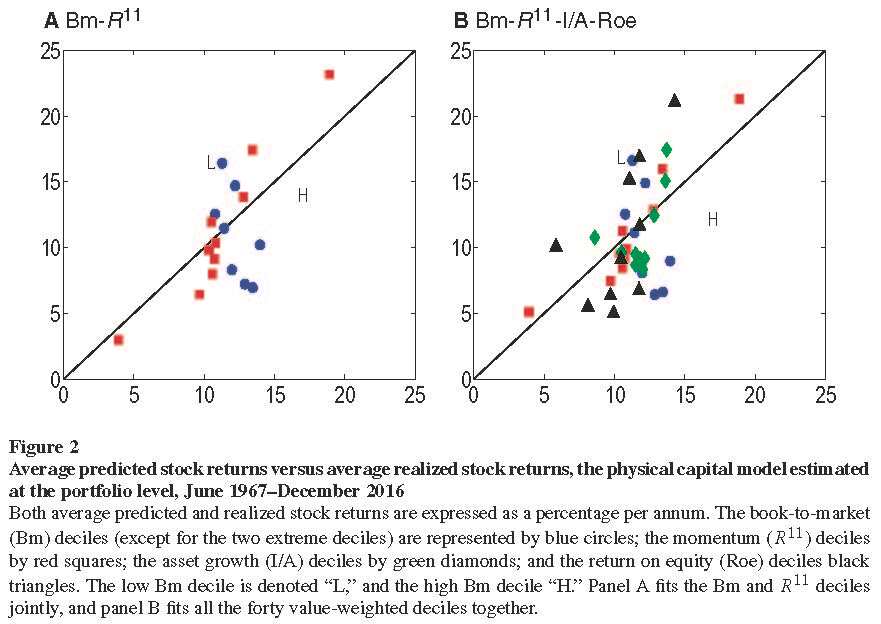

Our article titled “Aggregation, capital heterogeneity, and the investment CAPM” (Goncalves, Xue, and Zhang 2020) has just appeared in the June 2020 issue of Review of Financial Studies. A free copy is here as well as the internet appendix. A recurring critique of my structural estimation line of work started in Liu, Whited, and Zhang (2009) is that the parameter estimates appear unstable across different testing portfolios. This fair and important critique has guided our effort in the past five years. Thank you for arguing with me. Figure 2 from our latest publication replicates this difficulty. The parameter instability manifests itself as the failure of the baseline investment model in explaining value and momentum simultaneously (Panel A). The baseline model fits momentum but gets value upside down. Not surprisingly, the joint estimation failure persists once we add asset growth and return on equity deciles (Panel B). Figure 3 shows that the joint estimation difficulty has largely been resolved within an extended two-capital model with working capital and fixed, physical capital. Our article also offers a range of improvements in terms of measurement and econometric specifications. Perhaps the most important improvement is to calculate the "fundamental" (model implied) stock return at the firm level before aggregating it to the portfolio level to match with the portfolio-level stock return. Many important questions remain open. The measurement is all based on historical-cost accounting. Curious to see what happens with current-cost economic measurement. What about employment data? International data? Is it possible to develop ex-ante expected return measures out of this economic model that can compete with the prestigious and immensely important literature on implied costs of capital in accounting? Not sure, but I am eager to find out...

5 Comments

Umberto Sagliaschi

8/31/2020 11:58:00 am

I read with great interest your academic work, and I do agree on the underlying philosophy. The "anything goes" theorem is too often ignored, despite we all (investors) have experience of different tastes for risk and return. However, I have few questions/comments about your framework.

Reply

Lu Zhang

8/31/2020 11:04:11 pm

Thank you for your thoughtful comments. I've provided point-to-point responses in what follows.

Reply

Umberto Sagliaschi

9/1/2020 04:56:50 am

Thank you very much for your time and the very detailed clarifications.

Reply

Lu Zhang

9/1/2020 09:33:18 am

Certainly. I'll be happy to read and comment on your work. Thanks again for reaching out. Stay safe and healthy...

Reply

3/24/2021 11:18:25 pm

Totally unrelated, but do you think that practicioners should target I/A instead of value?

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Lu Zhang

An aspiring process metaphysician Archives

September 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed